Understanding “Understanding Comics”: How a Comics Textbook Works – by Lauren Bryant

- Dec 21, 2017

- 6 min read

Anyone who’s taken a class on comics has probably read Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. It’s one of the few textbooks about the medium, and discusses not any particular comic, but comics in general. McCloud addresses questions such as what makes something a comic, how old the medium is, and how it works. But how does the book itself work? Unlike most scholarly books, it’s not all text; it is in itself a comic. Though this seems to be a relatively new idea, McCloud’s not the only one to think of it. Nick Sousanis ended up in the news for being the first person to write a dissertation in comics form. Since it seems people are seeing some value in using this medium to write essays and textbooks, it’s worth examining how this form works with academic writing. I would argue that it can enhance the writing by making it more engaging, as well as by seamlessly weaving in visual examples and metaphors that reinforce learning. By taking a step back from McCloud’s Understanding Comics, we can begin to understand why the book has managed to become such a staple of academic comics literature.

The book, though illustrated, is still rather text-heavy, but the way words are depicted is different than most traditional texts. You may notice that in any given speech bubble, McCloud’s words are always capitalized and frequently bolded and italicized. This is standard conduct for comics; the capitalization has historically been done for legibility (particularly when hand-lettered), and italics and bolding help the reader imagine the verbal inflection of the phrases. However, I can guarantee that your English teacher would be quite upset if you did this in an essay. It is usually considered unprofessional, and possibly even confusing. But the comics form is not constrained by this standard. Though some people may argue that all textbooks, even those in graphic form, should abide by the same standards for lettering, I think that maintaining traditional comics conventions doesn’t detract from the work, but enhances it. First, it is keeping with the tradition of its subject matter, comics, by speaking in it’s own language. Second, by bolding and italicizing, it can create inflection that makes the work seem more conversational, as though McCloud is verbally speaking to the reader. This could make the reader more engaged with the text, particularly as it’s no longer flat and monotone. The inflection also helps him emphasize his key points. This ensures that the reader knows what things he finds important to understand. Though frequent bolding and italicizing are unusual for textbooks, McCloud’s unique use of the comics form integrates them in a way that makes sense for the medium and enhances his arguments.

The comics form also allows McCloud to do another unusual thing for academic writing; it establishes him as a character. Technically, all academic writing can be seen as being written from a certain perspective, whether it is that of one person or a whole team. However, the reader normally has to look beyond the veil to see this, as many authors separate their person from their work, sometimes refraining from using “I” pronouns at all. However, McCloud goes against this to the extreme. He draws himself as the narrator, featured on every page, making the audience glaringly aware of his presence. There is no mystery behind whose book this is; again, this makes it more akin to something verbal or physical, as though McCloud is a classroom lecturer. The use of this character McCloud has established is one of comfort and identification. The reader becomes increasing familiar with his personality and mannerisms, to the point he is almost like an acquaintance or friend by the end of the book. On the last page, he even apologizes for keeping you for so long, as though the audience was just there for a chat (McCloud 215). At the same time, McCloud realizes that it’s not really about him as a person, but a messenger. In the second chapter of the book, he explains that cartoony art styles help people identify with the characters. Because of this, he decided to draw himself in a simple style, so the audience wouldn’t be “too aware of the messenger to fully receive the message” (McCloud 36-7). In this way, McCloud strikes a delicate balance between revealing and hiding himself, showing just enough to make the audience listen, but not so much that they’d tune out. They can both engage with him and identify with him as they read. The use of the author as a character is something that the comics medium allows for and excels at, and McCloud utilizes this to help drive his points home.

Understanding Comics also has a non-traditional narrative style, allowing readers to see the thought process and discourse community behind the book. The most prominent example of this is found in the first chapter. To begin his discussion on comics, McCloud decides he should come up with a definition of comics. In a traditional essay, the author might dive straight into their conclusion. However, McCloud depicts himself revising his definition in front of an audience who is giving him constant feedback (McCloud 7-9). This not only humanizes him, showing that he doesn’t always get it right the first time, but reveals the wide world of comics discussion he is coming from. He is not the only one asking questions about what comics are, and he’s not claiming that he came up with the definition without the help of a wider discourse community. Whether or not he was actually asked all those questions (by other people or by himself) doesn’t matter; what is important is that showing this interactive situation welcomes the reader to join the conversation as well. It would be hard to illustrate this kind of dialogue in a text-only book, but the blend of image and words lets the reader jump into the narrative as though it were happening right before their eyes.

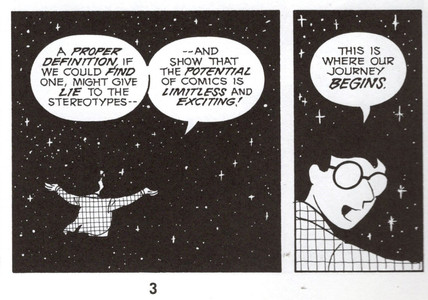

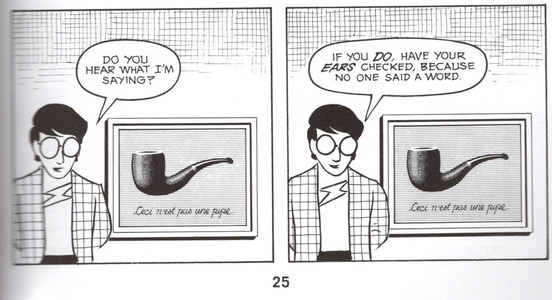

The visuals of the comic play a variety of important roles in the book, allowing McCloud to easily incorporate examples, demonstrate concepts, and reinforce points using visual metaphors. Like many academic works, Understanding Comics is saturated with references used to illustrate his point. Unlike text-based works, however, McCloud doesn’t need to pause and refer to “figure 4” to give an example. Because it is a comic, an image-heavy medium, he can pack in references to his subject matter (comics) whenever he wants. He can include a reference without even mentioning it, and it can still be noticed and enhance his point. The inclusion is seamless as well, because the images are blended with the explanation; they’re not forced to be separated like they are with text-based books, which have images and text in two different, defined spaces. This harmony of image and text also allows McCloud to demonstrate concepts at the same time he explains them. For example, on page 25, he discusses a painting called “The Treachery of Images,” and while doing so is constantly challenging the reader’s perception of what they are seeing. He heavily breaks the fourth wall by pointing out that his speech isn’t really speech; after all, it’s just ink on a page. In doing all this, he is revealing illustration’s magical power to make us translate symbolic representation into a real concept in our mind, even though it is nothing more than ink on paper. This kind of simultaneous explaining and demonstrating is possible with the written word, but it is more difficult, as it is only using one form of communication (writing), whereas comics use two (writing and illustration). Though McCloud uses this interplay to more thoroughly explain complex concepts, he also uses it in subtle ways to create visual metaphors, such as reinforcing the limitless potential of comics by drawing the expanse of space (McCloud 3). The visual nature of the medium allows concepts to be supported on multiple fronts, strengthening McCloud’s points and enhancing learning.

Understanding Comics is a prominent example of the potential of the comics form to convey complex academic ideas. Though the book is mostly meant to make visible the merits of other graphic works, it itself demonstrates some of the same virtues. Of course, it isn’t necessarily a perfect book, and I realize that the things I see as beneficial (such as conversational nature) may be seen as flaws by others. I don’t mean to suggest that all academic writing should be in comics form, either. Some tools simply work better for certain arguments, and in this case, the vocabulary of comics is a fitting instrument for McCloud’s discussion. However, it is worth considering comics as a medium for non-fiction, non-biographical books, as their unique form introduces a whole new host of narrative methodology. Though a lot of the book’s magic relies on its introspective subject matter of examining its own form, I think the medium could still be used as a tool to teach people about all sorts of things. Maybe as comics continue to gain traction in the academic world, we will see more ways that they can be used as means to learning. Here’s to the future!

.png)

Comments