Where Language and Identity Diverge in “The Arab of the Future" - by Lauren Allen

- Mar 7, 2019

- 3 min read

Updated: May 7, 2019

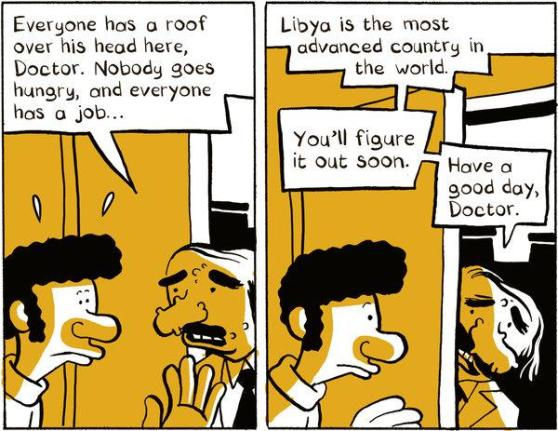

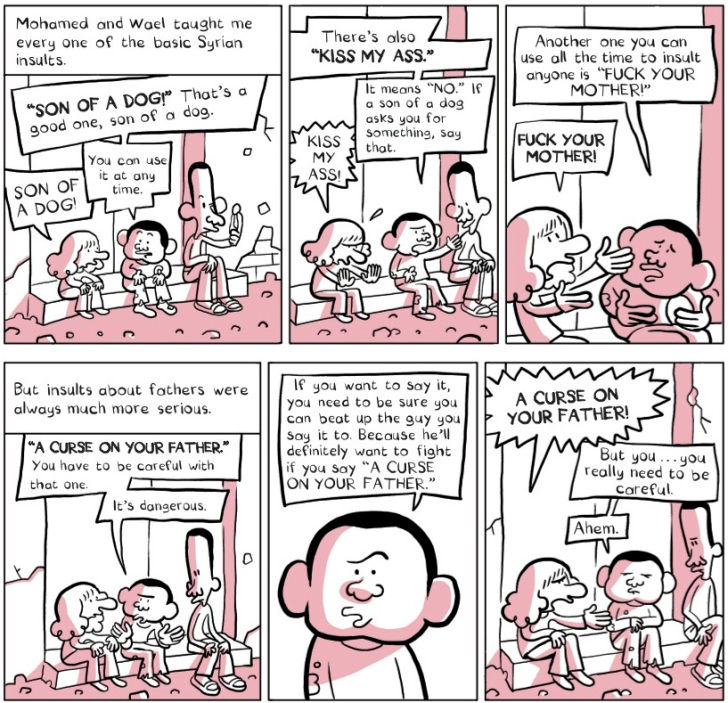

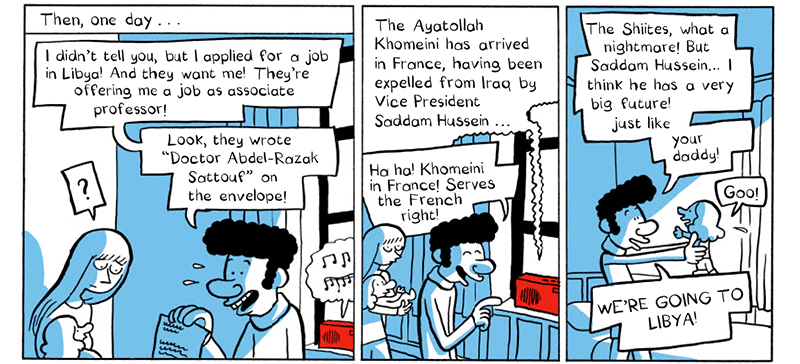

In the yellow, blue, and red graphic novel that follows young Riad from Libya, to France, to Syria, and back again, The Arab of the Future: A Childhood in the Middle East, 1978-1984: A Graphic Memoir takes us on a journey regarding identity, nationality, and transborder politics. Originally written in French, The Arab of the Future was translated to English by Sam Taylor in 2015, the same year of its’ publication. The memoir traverses the complex and personal dynamic of a transnational identity crisis in the face of a young, innocent, blonde-haired Sattouf.

Sattouf does not hold back when depicting his passive French mother Clementine and his often times bigoted and authoritarian Syrian father Abdel-Razak. As an autobiographical graphic novel depicting Sattouf’s adaptation to and at times violent understanding of his different nationalities, Taylor is challenged to adequately translate this recollection of Sattouf’s childhood hardship.

The narrative bounces back and forth between extremely mature reflection and very elementary thought-processes, highlighting the non-linearity and oscillation of remote boyhood memories. At times the switches between self-awareness and child-like obliviousness are abrupt and hard to follow, which could be attributed to Taylor, but could also reflect the challenges that come with grasping identity as a 5 year old under the omnipresent rules of Gaddafi in Libya, al-Assad in Syria, and arguably Riad’s oppressive father, Abdel-Razak, everywhere.

The translated text is unique in that it presents the English speaking reader with a personal account of history that has been often presented through a Westernized lens. Sattouf is not tasked to represent a people’s history and recount of Libya and Syria under authoritarian regimes, but does contribute to a nuanced understanding for Western audiences by virtue of Taylor’s translation to English. However, this translation comes with its own challenges. A text that is transnational like The Arab of the Futurerequires meticulous work to not only translate the French, but to grasp the different tones of all three of Riad’s homes and backgrounds. Sattouf makes this easier by color coding each country in order to create a new mood and environment for the reader to immerse into: yellow for Libya, blue for France, and red for Syria. Nonetheless, the question of whether Taylor was able to maintain objectivity when translating a scene of Riad’s friends in Syria beating a dog to death or the lack of private home space in Libya still remains. Trying to translate violence and violation without bias is a hurdle that Taylor may have just barely overcome.

Ultimately, the graphic memoir is one that challenges our conventional understanding of trauma, both through the uncertainty of memory, and the traumatic images of Riad’s childhood impossibly confined in the traditional three by three panel structure. Despite the few inconsistencies in tone, this translation is extremely successful in creating an image of Riad’s unstable childhood. While Sattouf is known for his humorous writing, this English translated text inevitably veers away from a comedic tone for the Western audience due to the differences and gaps in mutual cultural understanding when witnessing casual anti-semitism and violence. Translating a comic with this sort of political weight is challenging due to complex sound-images and linguistic variation, and Sam Taylor compliments Sattouf’s text with his interpanel work. This is Riad’s reality and may challenge the palate of the Western audience; however, this text is integral to a fuller understanding of a childhood that traverses authoritarian borders.

.png)

Comments