The Power of Non-Sequitur Transitions – by Kaitlyn McCafferty

- Feb 8, 2017

- 4 min read

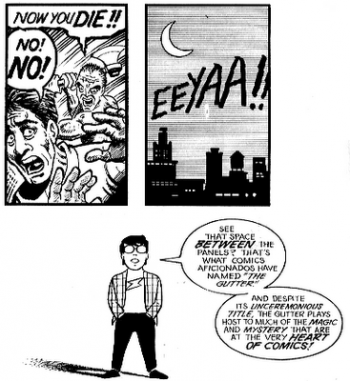

In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud finds tremendous power in the “gutter”—or the space between comic panels. In chapter three of his book, Blood in the Gutter, he asserts that audience closure between images allows for a type of reader involvement unique to the comics medium. He then goes on to categorize transitions into different types. This article will explore subject-to-subject, aspect-to-aspect, and non-sequitur transitions in relation to the power of audience closure. This idea of “power” is built upon the extent to which something necessitates viewer involvement to provoke new ways of thinking and foster the development of different perspectives.

McCloud first introduces subject-to-subject transitions, in which there is a distinct progression of time conveyed by images portraying separate subjects within the space of the scene. McCloud offers a powerful example of this transition through a murder scene, in which one panel depicts a man wielding an axe at his victim and the following shows the exterior of a house with a scream overlaying the image in text. McCloud asserts that the audience has “participated in the murder” by mentally constructing the action occurring in the gutter between the two panels. The reader decides “how hard the blow” was, as well as “who screamed [and] why” (68). This is where the power of subject-to-subject transitions lies: the ability to facilitate thought and imagination through reader participation.

Another transition McCloud defines is aspect-to-aspect—a transition that “bypasses time for the most part and sets a wandering eye on different aspects of a place, idea, or mood” (72). For example, imagine a sequence setting the scene in a kitchen. The first panel depicts a steaming kettle. It’s followed by a panel portraying a glove draped over the handle of an oven, then a panel of a tray of cookies resting on a stove. While the power of subject-to-subject transitions primarily lies in the ability to convey time, the power of aspect-to-aspect transitions lies is in their ability to create space. This space comprises not only of the physical, representative images portrayed, but of the other senses evoked through the connotative elements of the subjects. In this kitchen scene, sight, smell, sound, and even touch can all be evoked within a few panels. The scent and warmth of the cookies, the nurturing element of the glove, and the whistling of the kettle all work together to construct a much larger scene than what objectively exists within the confines of the panels. The reader mentally formulates this space using their own experience with the elements portrayed, filling in any gaps (such as the particular sound of the kettle, temperature of the room, or smell of the cookies) necessary.

The primary component that separates non-sequitur transitions from the other two is coherency. Non-sequitur transitions are constituted of a series of images that are seemingly unrelated to each other in any classic narrative form. Non-sequitur transitions are the most cognitively disruptive; they are the most uncomfortable. Take, for instance, a series of panels that first depicts an image of a refrigerator, then an abstract representation of a female nude, then finally, a meadow. Though the curator of these panels may not have had a specific narrative in mind, the viewer will try to draw associations between the images shown. This irresistible human tendency to put elements together to form a complete whole can be explained by Gestalt psychology, which explores the notion that human perception of a whole subject is based off of the sum of its parts. Non-sequitur transitions are powerful because of the diverse collectivity of every connotative and denotative element comprising the portrayed subjects. Non-sequitur transitions prompt the consumers of the images to see the individual subjects in a different way, making new mental connections and realizing contrasts between various elements of the world. This is extremely powerful. Though subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect transitions might necessitate reader involvement, they’re created through a much more directive authorship. Instead of drawing their own connections, the reader is led through a more set narrative.

These transitions can also be applied to narratives that take form in digital media, such as film. In the first chapter of Understanding Comics, McCloud differentiates comics from film by saying that comics are “juxtaposed sequential images” (8), as opposed to sequential images that all appear in the same place at different points in time to convey motion. In this way, film necessitates much less viewer imagination and mental closure. However, the viewer still perceives the transitions between scene frames as passages of time and space that do not objectively exist within the duration and space of the film and screen. Subject-to-subject transitions may repeat certain actions in order to convey motion better. A great example of this would be Jackie Chan’s fight scenes, which Chan speaks about in his “Every Frame A Painting: How to Do Action Comedy” episode. Chan does something in his action scenes that most American producers don’t: he will repeat an action in a separate shot in order to let the viewer’s eye adjust. This way, the impact of the action is clearer. This, of course, doesn’t occur in the linear timeline that viewers’ minds might perceive it to be. Meanwhile, aspect-to-aspect transitions may seem to suspend time in order to depict the mood or details of a space. Both of these transitions focus on separate subjects and images to formulate the space of a certain scene within the frame of the screen.

Though film’s ability to coherently convey the passage of time may lessen the power of subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect transitions the power of non-sequitur transitions will remain just as potent as it is in comics. The ability to draw connections between discordant images is a power that does not weaken in film. If anything, the usage of sounds that are objectively unrelated the images shown can amplify this effect of cognitive dissonance. Both comics and film as time-based hold spectacular power in their potential to challenge viewers’ perceptions of time and space. The discordancy of non-sequitur transitions exemplifies this power in a way subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect transitions cannot.

Works Cited

McCloud, Scott. Understanding comics:. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994. Print.

.png)

Comments