“Krazy Kat” Nov. 3, 1918: A Quick Formal Analysis – by Tyler Crissman

- Nov 30, 2017

- 4 min read

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat is notable for a number of reasons: it displays great and innovative cartooning, it has influenced many later cartoons, it list of fans includes notable persons such as T.S. Eliot and E.E. Cummings, it features a gender-fluid protagonist (even more uncommon then as it is now), and it interweaves subtexts regarding racial inequity (something Herriman personally knew, as a black man who made efforts to pass for white in both a profession and a nation rife with racism). A single, short article can do none of those distinctions justice. However, I will give an example of that first item on the list—excellent use of the comics medium—specifically in terms of form.

Here is the Krazy Kat page form November 3, 1918 (when newspaper strips had more room):

This page layout stands out for a pretty obvious reason: the whole thing is made of sloped panels. The reason for that is quickly apparent: the vignette revolves around rolling a stone down a hill. At first, things start out pretty simple. Krazy (the titular cat), Ignatz (the mouse), and the big rock all share the panel as Krazy begins to push, and again as the rock begins to roll. In the third panel, however, the boulder escapes the panel’s width even as the wider panel captures more space. Krazy, meanwhile, although moving forward in the story, has been pushed back in terms of page space. Krazy is further right and just as high on the page as in the previous panel. In the fourth panel, again the panel length increases and Krazy is pushed further back on the page (although this time a little lower). Using the growing distance between Krazy and the boulder (and in spite of the limited space of the page), the form of the page conveys the tumbling rock’s increasing speed. The trashed landmarks in the stone’s path, and the speed lines that pierce them, communicate the rock’s speed as well, but the way Herriman takes that speed to a formal level heightens and visceralizes the experience.

Suddenly, in panel five, Krazy skids to a stop behind the stone. Speed lines and debris still fill the air, evidencing the boulder’s only-recent halt, but it’s yet again the form that really makes the reader feel Krazy Kat’s last-second stop. Because Krazy had just been on the right side of the page a panel ago (and had an established spot on the right side of most panels), this change in their place within the panel is drastic. The implied time elapsed is very short, and so the halt Krazy makes is abrupt.

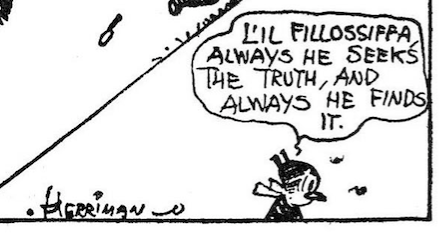

Krazy then proceeds to walk back up the hill to talk to Ignatz and wrap up the scene. Interestingly, at this point, the reading direction within the panels becomes a little unclear. Because comics are (in most English-language settings) typically read left-to-right and top-to-bottom, these sloped panels create ambiguity. Does Ignatz’s speech come first, being higher in the panel, or does Krazy’s speech come first, being further left in the panel? It turns out (based on the logic of the dialogue) that Krazy’s speech balloons are meant to be read first. This may well be simply a minor flaw of the page layout that is hard to avoid. However, unintentionally or not, I found it to slow my reading of the panels and come to notice something I might not otherwise have. Namely, the background is up to Herriman’s standard Krazy Kat tomfoolery, but in the case of this hill-based page, that aspect works in an interesting way. When I say tomfoolery, I mean that Herriman sculpts the comic’s backgrounds like a dream, with landscapes changing from panel to panel even when the action stays in the same place. Maybe a tree is replaced by a boulder, or a cliff changes shape, all unnoticed by the characters. Here, in the sixth and seventh panels, as Krazy marches up toward Ignatz, the strange-looking tree (or whatever it is in the background downhill of Krazy) is replaced by another tree, taller and further up the hill. Because Ignatz is visible and stationary in both panels, we can assume that this is the same view, so that tree in panel seven is indeed newly appeared and not a matter of panning the view further uphill. This matter of surreally shifting setting raises a question, however: in the panels where Krazy moves (or seems to move) to an entirely new segment of the hill, how much of the scenery shown is simply found further downhill, and how much is spontaneously spawned into existence? Perhaps it is all a matter of traveling downhill. Even then, though, when Krazy goes back up, how far back does Krazy go? If the panel skips ahead in time to Krazy reaching the starting point, then the small rock jut the boulder had been resting on is gone. Perhaps Ignatz came down a little ways and Krazy went only up so far as to meet him, but the full journey was still skipped over. Alternatively, maybe the segment of hillside we see Krazy and Ignatz on at the end is just above where the boulder landed, and the background has drastically changed from what it was before. When it comes to Krazy Kat, any of the above are possible.

That might not sound important, but in my opinion, that helps this page feel perhaps more like a dream than some other Krazy Kat pieces. I don’t have any kind of thesis on what factors might make a Krazy Kat page or strip more surreal (such as, in this case, the action occurring through a relatively large stretch of space), but this might make for some interesting study of Krazy Kat. Are the more stationary scenes less dreamlike? The only way to find out is to read a bunch of Krazy Kat…which I would highly recommend.

.png)

Comments