“FAKE” Review – by Chloe Spencer

- Art Ducko

- Nov 16, 2016

- 8 min read

Updated: Jun 2, 2019

DISCLAIMER: This review may contain spoilers for the manga.

What comes to mind when you see the word, yaoi? For many experienced otakus and manga readers, we know that it means “boys’ love or homosexuality.” These same readers also know that yaoi differs from shounen ai, in a very specific way: yaoi tends to depict sex, while shounen ai typically doesn’t, or does so less graphically.

When manga readers think of the word yaoi, they typically think of classics such as Junjou Romantica, Sekai Ichi Hatsukoi, Haru Wo Daite Ita, Sex Pistols, or newer, increasingly popular stories such as Hidoku Shinaide. These individual stories play out in the same way repetitively: normally, there is one character who is perceived to be as more powerful or is older than another character (example: Misaki and Usagi-san in Junjou Romantica). The characters struggle with their feelings as well as their sexual identities, and how these feelings affect their personal and public lives. Issues of identity tend to take the center stage in these stories. But more problematically in yaoi manga, sexual assault occurs: many of these relationships happen to start or develop after one character forces another character into sexual contact. Sexual assault is rarely addressed, and frequently, it somehow leads to a survivor of sexual assault falling in love with their perpetrator.

Now take what you know about yaoi and set it aside for now. Enter the world of FAKE.

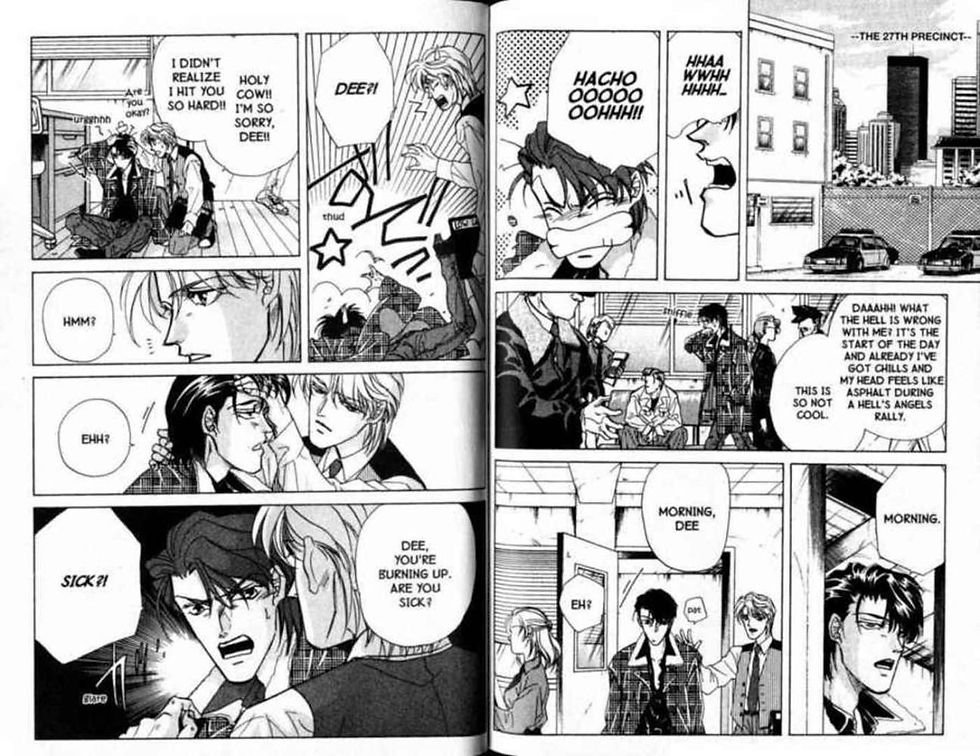

FAKE, a shounen ai-later-yaoi manga by Sanami Matoh, was originally written in the mid-1990s and finished in the early 2000s. The story focuses on the lives of police detectives Ryo and Dee who work for the fictional 27th precinct in downtown New York. Matoh plays with the idea of the cop-buddy formula that is frequently found in films such as Lethal Weapon and Rush Hour, pushing the relationship between Dee and Ryo from platonic to romantic.

When straight-laced and gentle Ryo meets the obnoxious loose cannon Dee, chemistry sparks between the two. But unlike most yaoi mangas that tend to quickly escalate a romantic relationship from step to step, these two take things at a much slower pace. After all, when Dee and Ryo first meet each other, they don’t like each other very much, and butt heads frequently. This is because of their strikingly contradictory personalities: Ryo has more tact and is somewhat reclusive, whereas Dee prefers to attack situations directly and is straight forward.

Dee develops feelings for Ryo first and almost immediately, but Ryo vacillates on his responses to him, as he is unsure of whether or not to take Dee seriously. In general, Ryo tends to have problems expressing feelings for others and pursuing romantic relationships, as he has been through some tragic experiences. Dee identifies as being bisexual, whereas Ryo doesn’t know—or doesn’t want to acknowledge–where he fits on the sexuality spectrum. One friend of theirs, Diana, refers to Ryo as her “closeted comrade.” It seems that before Ryo can honestly pursue a relationship with Dee, he has his own identity problems he needs to sort out.

That’s not to say that there aren’t romantic situations between these two before the end of the series: Dee kisses Ryo frequently, which Ryo rarely objects to (except in situations when they are around other people), and eventually, Ryo initiates physical contact between them as well. The issue of consent is more directly addressed in this manga than in other yaoi mangas. Though Dee frequently starts the physical contact, Ryo doesn’t object to it (and seems comfortable, which makes him wonder why he is) and he also tends to give Ryo an out. However, consent isn’t always present. Though Dee never assaults Ryo, there are several situations in which he pushes Ryo’s boundaries. Conveniently (and used in a comedic way), other people happen to walk in on them before they do anything. By the fourth volume, Dee becomes far more discouraged in his sexual advances towards Ryo. Internally, Ryo’s thoughts cross the page—“What? What am I supposed to do? I don’t know. I just don’t know anymore.” Though Ryo doesn’t outright reject Dee or say no, he is still confused. Dee sees Ryo’s confused face and doesn’t pursue the encounter further, saying, “Don’t worry… Besides, even though you don’t outright reject me, I’m not dumb. You always have this confused, worried, whatever look on your face. Because of that… I-I just can’t keep chasing after something I’ll never get.” Here, Dee demonstrates that he understands that consent is necessary in their interactions. Though he is disappointed and dejected by Ryo’s ambivalence, he acknowledges that without Ryo’s consent, and without giving him the space to consent, Ryo will likely not end up with him by choice, but by force. If Ryo ends up with him by force, that doesn’t mean that Ryo loves him—and Dee, who loves Ryo, wants Ryo to truly love him back. Ryo then apologizes for making him feel sad, and Dee says, “Don’t apologize. It’s not your fault, dammit.” Dee acknowledges that he’s part of the problem, and that his aggressive attitude doesn’t help Ryo sort out his feelings. Later in the same volume, Dee says to himself, “I want to be with him. I want to walk with him every step of the way. But I want him to want me.” So, while this manga still is definitely problematic in terms of how it addresses consent, it differentiates itself from other yaois by acknowledging it and letting it play a greater, more important role in these romantic interactions.

Additionally, FAKE differentiates itself from other mangas in how it navigates the less sexual aspects of the relationship. Unlike many other yaoi couples, Dee and Ryo are able to spend time alone together that is comfortable and intimate, and not just on a sexual level. They work on cases together; they take care of each other when they are sick and protect each other in the field; they have deep and meaningful conversations; they plan vacations and spend holidays together; and they tell stories about each other’s pasts in great detail. They get to a point where they know each other profoundly, where they can predict each other’s behaviors, and they become an excellent team. Not only do these details provide depth to their relationship, it makes them a more relatable couple.

It should also be noted that FAKE is different in how it incorporates women into the plot. Typically, women in yaois are one dimensional. They usually play the role of the beautiful viper-like seductress trying to steal one man’s partner, the overbearing family member, or the platonic-background-character-that-doesn’t-really-have-a-purpose. Diana and Carol are the two predominant female characters in the story—they are well rounded characters, given their own set of interests and abilities that make their impact on the story in their own, independent ways. For example, Diana is an FBI agent that occasionally stops by the precinct to help with a case. Initially, Diana is perceived as Ryo’s romantic rival, but as the story continues, her character shifts, and she becomes both a friend and a domineering authority figure. Carol, a younger character, is given room to develop her character over time, particularly in the side stories of each of the volumes. She serves as a sisterly figure in that she is kind and almost always willing to help others, but is dynamic in that she has a bit of a juvenile streak (she pickpockets), is intelligent, and is also a fighter.

But FAKE is also interesting in the themes that it pursues. Themes of identity and love are typical in yaoi mangas, but themes relating to family? Not so much, unless we’re talking about being pressured to follow tradition. In FAKE, Ryo becomes the adoptive father to an orphaned boy named Bikky, who is a bit of a troublemaker. While we see the relationship between Dee and Ryo develop, we also see that Ryo is learning to be a parent, and raise a child who errs on the side of delinquency–Bikky frequently robs parts off of bikes, gets into fights, and sometimes skips school. Because Dee is so close to Ryo, he also is learning how to be a parent, though his abrasive personality makes it difficult for him to be a positive and kind father figure. Carol, Bikky’s close friend, also plays an important role in the story.

Though she lives with her aunt, she too looks at Dee and Ryo as her father figures. The four form an inventive, sweet family. Vengeance is another theme that is explored in this manga, as Ryo hunts for his parents’ killer—and justice, of course, also plays an important role in a cop manga. Loneliness and depression are another two themes that are addressed through Ryo and Dee’s stories, as each man is learning to cope with the tragedies from their past.

But what is the most intriguing issue that is explored in FAKE is racism. Typically, race isn’t discussed in a manga, and that is because the characters are primarily Japanese. Most of the characters in FAKE are white, but Ryo is half-Japanese, and Bikky is black, but had a white mother. Bikky is teased because he has blond hair like his mother, and is called an “Oreo” and other racist names. In one volume, Ryo is almost the victim of a hate crime because he is Japanese. Additionally, in another story in which Dee and Ryo are working on solving a series of gruesome murders, the two meet the father of one of the victims, who is black. Before he had been able to identify her body, coroners performed an autopsy. This angers him, causing him to say, “You think you can just cut her up any which way you like for your so-called autopsy without even asking anyone? I’m used to the rest of society treating us blacks like second-class citizens—I know that drill too well—but I sure as hell didn’t expect that sort of treatment from you boys in blue, too.” Though Matoh has faltered in recognizing that in the United States police forces have frequently contributed to systemic racism, she is attempting to do something that is quite noble, and very different from that of other mangakas. Matoh had the option in writing FAKE to ignore issues of race, but chose to write it into the work because she perceived it as being important. Very few mangas deal with issues of race, and very few mangas have characters of color (characters are primarily Japanese or white), nor choose to acknowledge the perspectives of characters of color. But Matoh wants her readers to engage with discussions of race. She continues the discussion by having Ryo and Dee talk about what happened with the man, and they (albeit briefly as they are in the middle of a case) talk about racism and prejudice. This is another theme that sets FAKE aside from other yaois, and other manga in general.

Ultimately, FAKE challenges the idea of what a yaoi is, and challenges the conventional stereotypes, story ideas, and plot devices that are typically found in the genre. Unique in the themes that it addresses as well as the character dynamics, but comedic and action packed-enough to maintain the reader’s attention, FAKE is a manga that has left a lasting impression within the manga world. Influences of the manga and Matoh can be found in the works of Kazuma Kadoka as well as other comics such as Honto Yajuu. While FAKE is problematic in some ways, its intelligent and carefully crafted stories serve to inspire a new generation of readers, writers, and artists to create stories that challenge the norm.

Sources

Matoh, Sanami. Fake. Vol. 1. Los Angeles, CA: TokyoPop, 1994. Print.

Matoh, Sanami. Fake. Vol. 2. Los Angeles, CA: TokyoPop, 1994. Print.

Matoh, Sanami. Fake. Vol. 4. Los Angeles, CA: TokyoPop, 1996. Print.

Matoh, Sanami. Fake. Vol. 6. Los Angeles, CA: TokyoPop, 1999. Print.

Matoh, Sanami. Fake. Vol. 7. Los Angeles, CA: TokyoPop, 2000. Print.

.png)

Comments