“32 Stories” Review – by Tyler Crissman

- Art Ducko

- May 26, 2016

- 3 min read

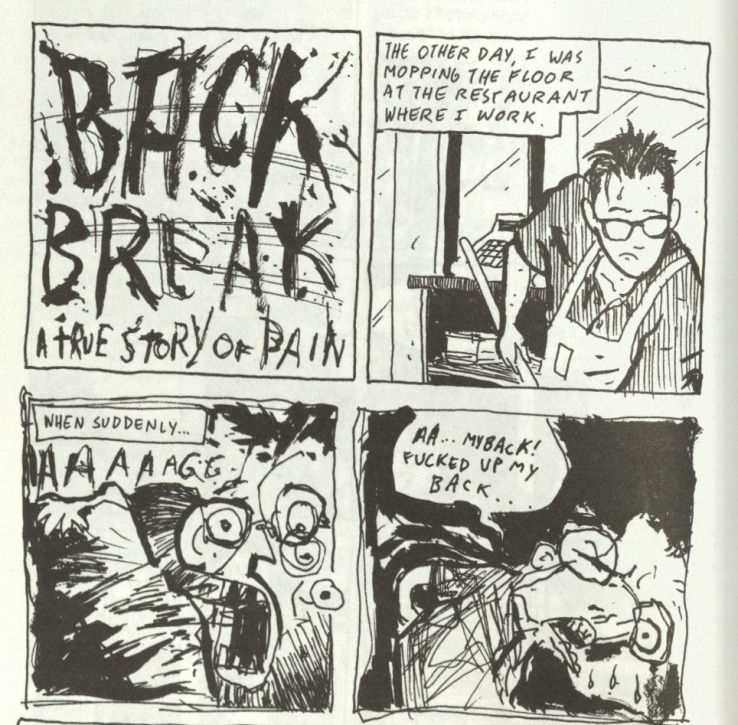

You’re not quite sure why you’re drawn in, but you know that you are. That is a feeling that Adrian Tomine’s short comics collected in 32 Stories can induce. When I first started reading 32 Stories, I wasn’t sure what to think, but I knew something made me keep reading. The more time I spent with it, the more I grew to like the odd little book, and appreciate its genius. A two-page story narrated by a disturbingly paranoid man with a dog-centric conspiracy theory. Inner monologues and inky monochrome. Bizarre dreams made into surreal, panelized vignettes. Slice-of-life stories that range from wryly humorous, to sad, to off-the-wall weird. Perhaps that array of phrases communicates some of what this book contains.

Some of the stories are autobiographical (or partly so), even self-referentially mentioning the creation of said stories, in various ways, in some instances. Others are presumably less autobiographical, and the protagonists range from your average neurotic youth, to your last-place pick for a desert island buddy. Quirks and anxiety abound, applied to comedy as well as to poignant, atmospheric pieces. There is angst in the mix, and although that word comes with disreputable baggage, these Optic Nerve stories are well-composed works of comics (in case my opinion wasn’t spouted out enough yet). And yes, the words “angst” and “youth” above are good indicators of Tomine’s youth at the time. He simply set out on a comics career and kept it going.

Optic Nerve began in 1991 as Adrian Tomine’s purely self-published (i.e., drawn and then Xeroxed) comics. At the time, he was only in high school. There is something romantic about the utterly self-published comics career, and Tomine’s subsequent progression to an achieved cartoonist is inspiring. Eventually, in 1994, Drawn & Quarterly became the series’ publisher (as well as owner of, probably, the best comics publisher name). Since then Tomine’s career has further progressed, of course, but to discuss 32 Stories—even in the small sample contained, the change in art, writing, and production value over time is visible. That doesn’t mean that the earlier stories are worse and the later ones better; it’s just a matter of change, and there are merits to all the different styles of stories in the collection.

One constant in all the stories is an effective use of black and white. A few of the later stories utilize half-tone greys, but most of the art is not just monochromatic but sheer black and white. Tomine achieves a great level of both clarity and compositional virtuosity. He’s not afraid to use swaths of black or heavily shadowed people and things, but never loses legibility. Even when Tomine’s style is rough and gritty, it maintains clarity. Speaking of roughness, his panel borders are often wobbly or crooked, but (at least, by the middle of this collection) made so with skill. Those borders add character to the comics, and I miss them in the later portion of the book, when Tomine used a “cleaner” look.

All stylistic quibbles aside, this admittedly short, but pithy, volume has a varied array of short-story comics. There is something enticing, addictive, and eloquent about the brevity of the stories. All of the stories are good comics, and some are fantastic. “Haircut” (maybe my favorite of the 32 stories) is, in my opinion, a masterpiece, especially for a three-page comic. I won’t say a thing more about it, lest I spoil it for anyone. Regardless, it isn’t the only brilliant piece in there. But I’ll leave that up to anyone interested to read 32 Stories to find out for themselves.

.png)

Comments